Originally printed in the March/April 2024 issue of Down Country Roads Magazine

Something new is stirring. It is the in-between, that elusive time when seasons collide and blend and bend and break. Not yet spring, but no longer truly winter. A few more storms may be all it takes for winter to wear herself out and peacefully subside, a few more days and nights of wild wind and heavy snow, waking to a transformed landscape.

We aren’t yet done with frosty mornings that nip the nose and fingers and rosy up the cheeks. We aren’t yet done with heavy coats and encumbered action. We haven’t seen the last of the delicate flowers that frost the windowpanes. We haven’t seen the last of the iced-over backs of the heavy cows, or broken the last ice on the dams. There may yet be a little more of that.

But we have tasted the springtime in the warming air; we have heard the sound of water running from rooftops, and have smelled the earthy perfume of a thaw. We have sunk into the softening earth, and felt it yield to our footsteps. We have felt those telltale warm breezes, and seen the first of the springlike clouds, even ones dropping hopeful rain, virga, somewhere higher than the earth. We have felt the sunlight later, and seen the sunrise earlier, and we know—we know—that springtime will come. Winter is long in the Hills. But she never lasts forever.

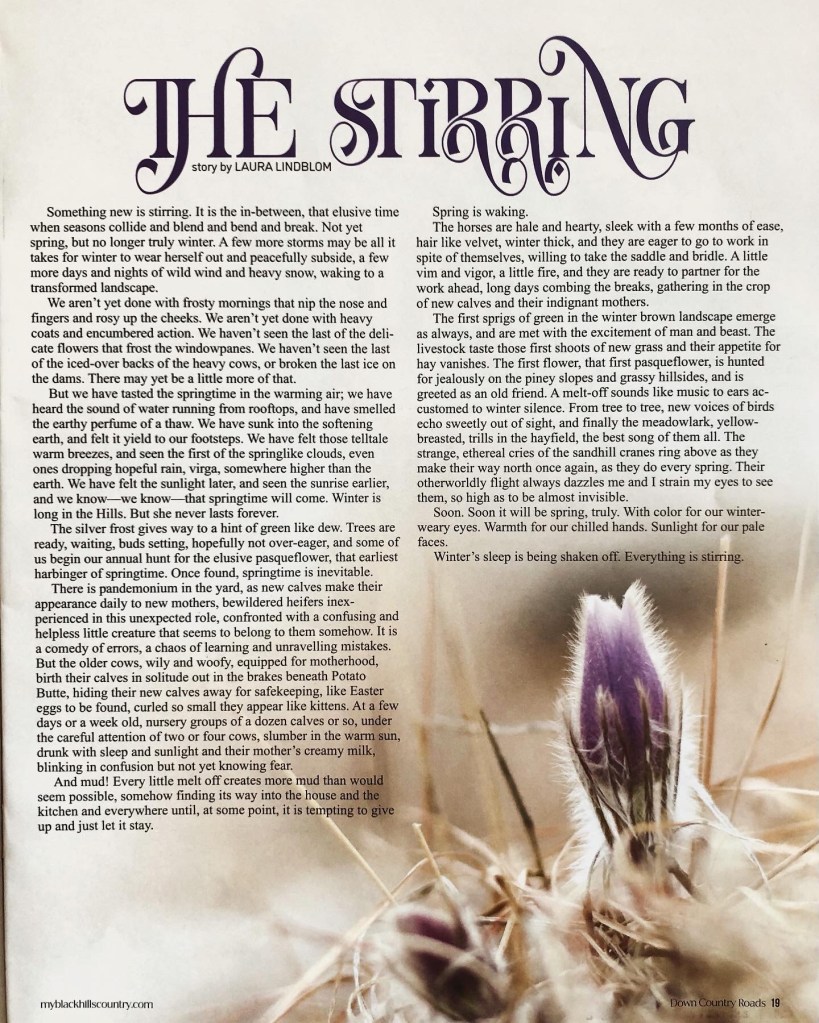

The silver frost gives way to a hint of green like dew. Trees are ready, waiting, buds setting, hopefully not over-eager, and some of us begin our annual hunt for the elusive pasqueflower, that earliest harbinger of springtime. Once found, springtime is inevitable.

There is pandemonium in the yard, as new calves make their appearance daily to new mothers, bewildered heifers inexperienced in this unexpected role, confronted with a confusing and helpless little creature that seems to belong to them somehow. It is a comedy of errors, a chaos of learning and unravelling mistakes. But the older cows, wily and woofy, equipped for motherhood, birth their calves in solitude out in the brakes beneath Potato Butte, hiding their new calves away for safekeeping, like Easter eggs to be found, curled so small they appear like kittens. At a few days or a week old, nursery groups of a dozen calves or so, under the careful attention of two or four cows, slumber in the warm sun, drunk with sleep and sunlight and their mother’s creamy milk, blinking in confusion but not yet knowing fear.

And mud! Every little melt off creates more mud than would seem possible, somehow finding its way into the house and the kitchen and everywhere until, at some point, it is tempting to give up and just let it stay.

Spring is waking.

The horses are hale and hearty, sleek with a few months of ease, hair like velvet, winter thick, and they are eager to go to work in spite of themselves, willing to take the saddle and bridle. A little vim and vigor, a little fire, and they are ready to partner for the work ahead, long days combing the breaks, gathering in the crop of new calves and their indignant mothers.

The first sprigs of green in the winter brown landscape emerge as always, and are met with the excitement of man and beast. The livestock taste those first shoots of new grass and their appetite for hay vanishes. The first flower, that first pasqueflower, is hunted for jealously on the piney slopes and grassy hillsides, and is greeted as an old friend. A melt-off sounds like music to ears accustomed to winter silence. From tree to tree, new voices of birds echo sweetly out of sight, and finally the meadowlark, yellow-breasted, trills in the hayfield, the best song of them all. The strange, ethereal cries of the sandhill cranes ring above as they make their way north once again, as they do every spring. Their otherworldly flight always dazzles me and I strain my eyes to see them, so high as to be almost invisible.

Soon. Soon it will be spring, truly. With color for our winter-weary eyes. Warmth for our chilled hands. Sunlight for our pale faces.

Winter’s sleep is being shaken off. Everything is stirring.